This is the first of a two part blog focusing on lenses for evaluating systems change. The second post, to follow, will address methods for evaluating systems change

What is systems change?

Systems change is a bit of buzz phrase in the charity world at the moment. But what does it mean? While there a several definitions, the common thread refers to addressing root causes of social problems, recognising that people and the mechanisms they operate in are interlinked.

Quite often, as external evaluators, we are invited to evaluate charity programmes which have a strong focus on systems change. This blog post outlines what I’m learning about evaluating systems change. Disclaimer alert! This is very much a work-in-progress and with almost every evaluation I work on, new angles for evaluating systems change pop up!

Where systems change gets tricky and sticky!

The above definition of systems change is tricky within the context of a charity-led programme. Based on a few programmes we have worked on recently, I am observing some of the following about systems change programmes:

- It can take a considerable amount of time for stakeholders to get “on the same page” about which system(s) or part of a system(s) needs improving. Often, at the start of a programme, there is an assumption that stakeholders (often multi-agency) have a shared understanding of the change required. But this is often challenged once the programme begins delivery, with different stakeholders having a different perspective on what is required or, indeed, what the problem is

- Often the systems we seek to change are broken and incoherent. Often the system doesn’t need to be “changed” but needs to be “designed” or “redesigned” from scratch

- Typically, programmes run for 1-3 years (or more if you’re lucky!) and within this time frame it is not always feasible to change an entire system – this is often beyond the sphere of control of a time-limited programme

- Within a 1-3 year time frame, contexts can change. New governments, global pandemics, economic downturns, Brexit….so the systems a programme may seek to influence are in flux

- There are “invisible” parts of a system which can be taken for granted. For example, understanding the power dynamics (who makes decisions?) and the values that stakeholders have (are they aligned?). Understanding these things takes time. And influencing them is often a pre-condition to long term systems change – sometimes these pre-conditions are neglected in programme design

- There can be lack of clarity about whether the programme seeks to influence change at a local/regional level or at a national level

Lenses for evaluating systems change

Based on the above sticky-points, I am developing different “lenses” for evaluating systems change. There are two broad lenses that I find helpful. A little disclaimer! This is very much a work-in-progress and with almost every evaluation I work on, new angles for evaluating systems change pop up! So, the two lenses I am currently working with are:

- A warm systems lens – this applies with then intended change is expected to take place at a local and/or sub-sector level, where there is broad willingness, openness, and receptiveness to change.

- A macro systems lens– typically take place at a more strategic and complex level. This evaluation lens is applied when there is a need to instigate / influence change amongst external stakeholders i.e. outside the lead organisation (e.g. a charity seeking to see changes within statutory provision). This lens applied when there may be reluctance within amongst some stakeholders to acknowledge the problems within the system.

Lets look at each lens in turn

Warm systems evaluation lens

Some examples of systems which would be evaluated through the lens of “warm systems” include:

- A school who recognises that they work with asylum seeking children but aren’t connected with other local agencies

- A local authority who recognises that young people in their area experience high levels of trauma due to exploitation and would like to improve trust with services

- A charity who observes social isolation amongst older people in care homes and would like to raise awareness of the role digital technology could play

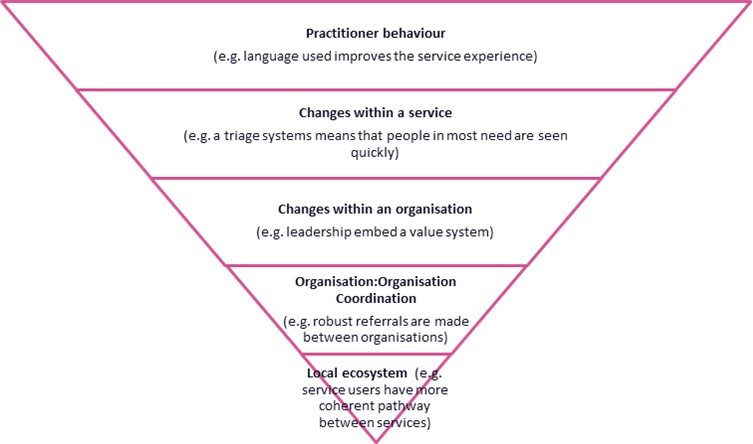

Figure: warm systems evaluation lens

Once we have clarity on which aspect (or aspects) of the system a programme is trying to address it is possible to agree and measure outcomes. The evaluation works best when it is grounded in an understanding of what a programme is trying to do.

Macro systems evaluation lens

Some programmes seek to address systems which are not necessarily “warm” and may be beyond an immediate community or locality. Often, these initiatives seek to influence changes to policies, legislation and/or wider public attitudes. This is often where change-agents recognise that systems (including process, policies and structures) and sometimes contribute to the social problems (even those that they seek to address!) and a larger-scale change to the architecture of the systems are required.

Some examples of macro systems change include:

- Reinstating legal aid for refugees seeking family reunion

- Reducing the number of young people who are excluded from school

- Reducing homelessness for people with substance misuse problems

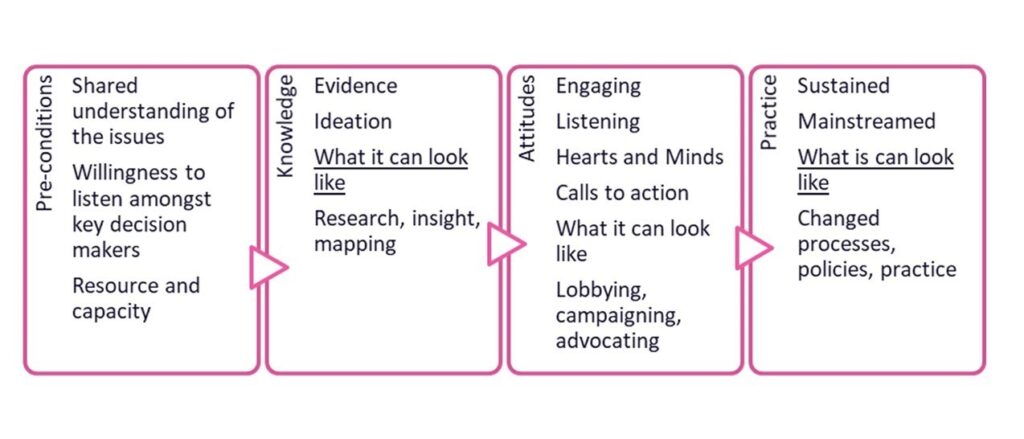

Oftentimes, such challenges call for a multi-agency and statutory sector response. When evaluating this work, I consider a macro systems evaluation lens as illustrated below. There are four clusters of work which I’m observing – and there is some overlap and flow between the clusters (they don’t fit as neatly into the boxes as the diagram suggests!). These clusters are:

- Preconditions to systems change i.e. having resource and a shared understanding of the challenges

- Knowledge i.e. building knowledge of what the challenge and tabling possible solutions

- Attitudes i.e. working with decision makers to influence decision making

- Practice i.e. the change we want to see

Figure: macro systems evaluation lens

When evaluating systems change at macro-level I like to begin by getting clear on which cluster (or clusters) of activities are the primary focus of a programme and build a Theory of Systems Change around that. For example, a programme may focus on preconditions, knowledge, attitudes AND/OR practice – it is often unrealistic for a programme to aim to address all three at the same time. Sometimes this evolves throughout a programme as things are learned about the system. And often it is not linear – programmes “ping” between clusters. But I find getting relative clarity of where programmes intended focus is helps to build a more representative Theory of Change.

Following the development of a Theory of Systems Change, we then develop an evaluation framework and associated methodologies. I’ll save that for another blog post!